简体中文

繁體中文

English

Pусский

日本語

ภาษาไทย

Tiếng Việt

Bahasa Indonesia

Español

हिन्दी

Filippiiniläinen

Français

Deutsch

Português

Türkçe

한국어

العربية

A ‘Buy Everything’ Rally Beckons in World of Yield Curve Control

Abstract:LISTEN TO ARTICLE 5:56 SHARE THIS ARTICLE ShareTweetPostEmail Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell

As central banks pump trillions into the world economy, investors are setting their sights on what could be the next big thing in global monetary policy: yield curve control.

The strategy, which involves using bond purchases to pin down yields on certain maturities to a specific target, was once deemed an extreme and unusual measure, only deployed by the Bank of Japan four years ago after it became clear that a two-decade deflationary spiral wasnt going away.

No longer. This year, the Reserve Bank of Australia adopted its own version. And despite officials attempts to cool it, speculation is rife that the U.S. Federal Reserve and Bank of England will follow later this year.

Should yield curve control go global, it would cement markets perception of central banks as the buyers of last resort, boosting risk appetite, lowering volatility and intensifying a broader hunt for yield. While money managers caution that such an environment could fuel reckless investment already stoked by a flood of fiscal and monetary stimulus, they nonetheless see benefits rippling across credit, equities, gold and emerging markets.

“It depends on the form and the price but broadly speaking its the green light to carry on with the QE trade -- buy everything regardless of valuation,” said James Athey, who manages $3.1 billion at Aberdeen Standard Investments in London.

Boost for Bonds

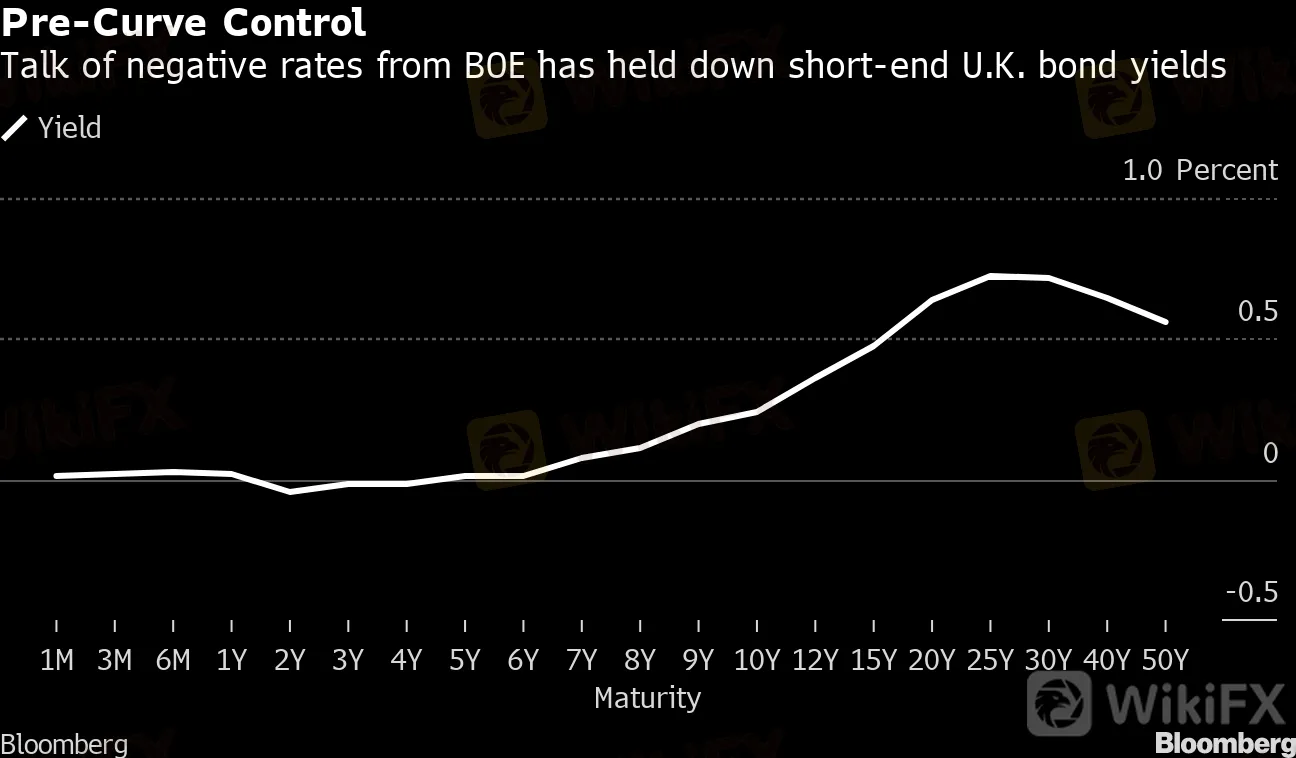

While the BOE didnt discuss yield curve control on Thursday, some analysts think it could ultimately target five-year notes at a rate of 0.1%, flattening the yields out until that maturity.

That could send money flowing into shorter maturity bonds and trigger a sell-off in volatility. Demand for shorter maturities could drive up rates on longer peers -- a mixed blessing for pension funds and life insurers, which could see their existing holdings devalued, but be able to buy new assets for less.

Pre-Curve Control

Talk of negative rates from BOE has held down short-end U.K. bond yields

Bloomberg

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said the usefulness of the policy “remains an open question” on June 10. While most expect a low-yield target for shorter maturities, potentially as soon as September, Societe Generale SA sees a case for focusing further out the curve. Five- and seven-year Treasuries may rally if the Fed looks to go beyond controlling just the front end.

Where central banks set their target will be key, and could send assets swinging either way. A 50-basis-point target on the 10-year Treasury yield would spark a bond rally and flatten the curve alongside a probable rise in equities. However, a full percentage point could see bonds bear steepen and trigger a sell-off in shares, said Aberdeen Standards Athey.

Credit Surge

Capping interest rates would help by ensuring corporate borrowers continue to benefit from attractive financing rates. Lower yields in longer maturities would assist investment-grade companies, which tend to issue longer-dated debt than lower-rated borrowers. Meanwhile, junk borrowers would reap the rewards of the general boost to market sentiment.

Companies with high debt loads such as airlines and energy could get a lift, said Charles Diebel, who manages $2.6 billion at Mediolanum SpA in Dublin. U.K. banks could also gain as lenders will have escaped the crushing effect of negative interest rates.

“It will allow the whole rating spectrum of fixed income credits to borrow at incredibly cheap absolute levels during a time of much uncertainty and would certainly be very bullish,” said Azhar Hussain, head of global credit at Royal London Asset Management.

Carry Trade

Lower rates in the U.S. could weaken the dollar and help riskier currencies like the South African rand and Mexican peso. Carry trades involving the Indonesian rupee and the Russian ruble could also benefit, as well as Group-of-10 currencies like the Australian dollar and Norwegian krone, according to Vasileios Gkionakis, head of foreign-exchange strategy at Banque Lombard Odier & Cie SA in Geneva.

The move could also send dollars flowing into carry trades targeting U.S. assets. These could include mortgage-backed securities, as well as sovereign, supranational and agency bonds.

Bubble Risk

Of course, such a widespread bullish outlook comes with risks, especially at a time when asset valuations are near extremes. A rally in U.S. stocks has pushed estimated price-to-earnings to the highest in almost two decades.

Meanwhile, 10-year yields are negative for nine of 25 developed markets tracked by Bloomberg, while the rest stand well below their one-year averages. It‘s a precarious bubble that could eventually burst, should the wall stimulus spur inflation down the road and eat into investors’ profits.

| Read More |

|---|

|

Global Lessons, Challenges

While most asset classes stand to gain from a global wave of yield curve control, investors may want to heed lessons and challenges from different regions.

Since the BOJ started the policy in 2016, it has largely succeeded in tethering the 10-year rate at around 0%. As for the RBA, it began pinning the three-year yield at 0.25% in March. Yields on longer maturity bonds rocketed then eased after the announcement, and the spread between three-year and 10-year yields remains around 30 basis points wider than in mid-February.

For the European Central Bank, the challenge would be the multiple interest-rate curves under its remit. The ECB has acknowledged the importance of keeping borrowing costs low across all bond maturities, without committing to an explicit yield curve control policy.

Regardless, the notion that central banks are approaching some sort of curve control is here to stay. A key lesson from the 2008 crisis was that policy makers need to intervene quickly, and investors now expect them to consider any weapon at their disposal.

“Policy makers tightened up the banking system so much that the markets became too big to fail,” said Mark Nash, the head of fixed income at Merian Global Investors in London. “Now they have no choice but to keep them working.”

— With assistance by Alice Gledhill, and Stephen Spratt

Disclaimer:

The views in this article only represent the author's personal views, and do not constitute investment advice on this platform. This platform does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness and timeliness of the information in the article, and will not be liable for any loss caused by the use of or reliance on the information in the article.

WikiFX Broker

Latest News

TradingView Brings Live Market Charts to Telegram Users with New Mini App

Trump tariffs: How will India navigate a world on the brink of a trade war?

Interactive Brokers Launches Forecast Contracts in Canada for Market Predictions

Authorities Alert: MAS Impersonation Scam Hits Singapore

Stocks fall again as Trump tariff jitters continue

INFINOX Partners with Acelerador Racing for Porsche Cup Brazil 2025

Regulatory Failures Lead to $150,000 Fine for Thurston Springer

April Forex Trends: EUR/USD, GBP/USD, USD/JPY, AUD/USD, USD/CAD Insights

March Oil Production Declines: How Is the Market Reacting?

Georgia Man Charged in Danbury Kidnapping and Crypto Extortion Plot

Currency Calculator